Will Israeli watermelons become renewable fuel in the future?

August 6, 2020The Malali watermelon is known for its large crunchy seeds, a popular snack among Israelis. However, 97 percent of the fruit is discarded in the field as waste. A new Israeli study shows that this waste could be used to produce renewable fuel

Hot Israeli summer days are the perfect time to snack on a deliciously fresh slice of sweet and chilled watermelon. The Malali watermelon is less known for its tasty pulp, but rather it’s crunchy seeds.

Unfortunately, the melon seeds are the only part of the watermelon that is being used. The rest of the fruit is thrown into the field where it goes to waste.

However, a new Israeli study has found that the fruit residue can be used to produce ethanol, an alternative biological fuel for vehicles, which is also the main ingredient in alcohol.

A different kind of melon

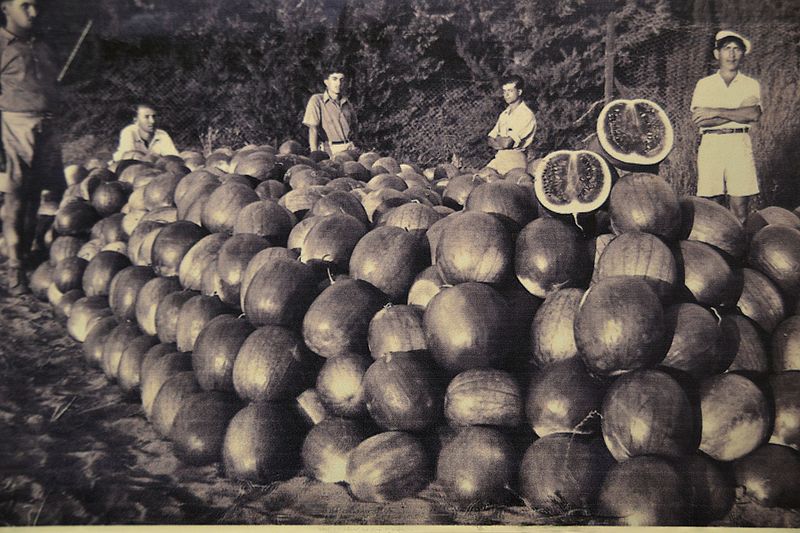

The Malali watermelon is named after the village of Kfar Malal in central Israel, where the variety was first cultivated. Research suggests that the Malali variety is a cross between the local Mahasni and the Chilean Black. Today the Malali grows in Israel on a total area of 40,000 dunams.

Contrary to other Israeli varieties, which contain few to no seeds, the Malali watermelon is riddled with them. The local watermelon plants provide the nut industry with 2,800 tons of seeds a year.

At some point in the growth of the watermelons, the farmers stop watering them for about two weeks, which induces stress on the fruits. This stress encourages the melons to take care of the “next generation” by accelerating the ripening process of the seeds.

When the seeds are ripe, a combined harvester separates the seeds from the fruit and collects them.

However, the pulp and the peel, which together make up 97 percent of the watermelon’s weight, are not collected but discarded in the field. “The wastage here is clear and glaring,” says Associate Professor Yoram Gerchman of the Department of Biology and Environment at the University of Haifa and the Oranim Academic College, who oversaw the research conducted by one of his students in his laboratory.

200 tons of carbon dioxide

This waste also has environmental consequences. The pulp accounts for 59 percent of the Malali watermelon weight, but it is not sold as food because the Malali variety is not famous for its taste. Therefore, every year, about 56,000 tons of watermelon pulp is wasted in the fields, 5,600 tons of which are sugars. When various bacteria and fungi in the soil begin to feed on the sugars, they release greenhouse gases (mainly carbon dioxide), which contribute to the greenhouse gas effect and thereby to the climate crisis.

The researchers estimate each year a total of 8,200 tons of carbon dioxide are emitted into the atmosphere on account of watermelon waste. Additional carbon dioxide is released during the watermelon production process due to the use of agricultural tools, fertilizer, and water – all for a product, of which 97 percent is wasted.

Turn the sugar into fuel

In the new study, which was conducted at Gerchman’s laboratory as part of a bachelor’s project in biology by his student Maya Maliniak, the researchers examined the possibility of producing ethanol from watermelon pulp. There are now ethanol-fueled engines, but even a regular gasoline engine can run on gasoline containing up to 10 percent ethanol. One of the benefits of using bio-ethanol, and biofuels in general, is reducing fossil fuel dependence: coal, oil, and natural gas, whose reserves are depleted without the ability to regenerate and whose use generates substantial greenhouse gas emissions.

However, the use of ethanol also has disadvantages, the most prominent of which is that for its production, agricultural lands are used for industrial crops or non-food crops.

In various countries, grains and other edible plants (mainly corn and sugar cane) are explicitly grown for ethanol production, a phenomenon that exacerbates global food shortages and raises food prices. In the small nation of Israel, where it is still necessary to import most of the grain seeds that are consumed, there is currently no ethanol industry. Using watermelon waste, however, will allow ethanol production without wasting agricultural land.

When a watermelon is not watered, it loses its liquids, but not its sugar content. Therefore, the sugar percentage in ripe Malali watermelons is high, up to 18 percent, compared to only 10 percent in the edible varieties.

In addition to ethanol, the researchers also examined the possibility of using watermelon waste to produce lycopene: a dietary supplement sold in health food stores as an antioxidant.

Lycopene, which is present in large quantities in watermelon and what gives it its red color, is usually produced from tomatoes grown specifically for this purpose. “Watermelons have a large amount of lycopene that is simply thrown into the field,” says Gerchman. According to him, the profit from the utilization of lycopene in watermelons can help farmers. “Farmers do not earn much from watermelon seeds, and agriculture is generally a very unprofitable field. The farmers would welcome any additional amount.”

“The easiest waste I’ve ever worked with”

In the new study, the researchers collected several dozens of watermelons during the harvest period in the Jezreel Valley area and fermented the watermelon juice into ethanol. “It turns out that watermelons are fermenting very well,” says Gerchman, who has researched ethanol production from various materials, such as pruning waste, olive waste, and paper waste. “This is the easiest waste I have ever worked with.”

In addition, the researchers found that each watermelon can produce eight capsules of lycopene.

Gerchman and his team are currently working on raising funding that will allow them to advance to the next stage of the research. This next stage will include larger quantities of watermelons and will be carried out outside the laboratory conditions – in the agricultural field, using tools used by watermelon farmers.

Gerchman hopes that in the future, the production of ethanol from watermelon waste will become a reality that will be implemented in the fields.

“It’s not complicated to develop a combine harvester that would transfer the watermelon juice to the tanker instead of throwing it in the field,” Gerchman says.

“The tanker would transport the juice to a container near the settlement where it is fermented to ethanol. Afterward, another tanker would take the ethanol to gas stations or chemical companies. My vision is that this will happen in any settlement that has watermelon fields,” he adds.

First step towards ethanol production in Israel

It should be noted that since the watermelon industry in Israel is rather small, the total amount of ethanol that can be produced with this method is according to the researchers only 2,900 tons per year (for comparison, the amount of gasoline used in Israel each year is 3.2 million tons).

Beyond that, the growth is seasonal, so the waste is only available at certain times of the year. However, according to Gerchman, extracting ethanol from the watermelons is still worthwhile.

“When it comes to setting up an ethanol plant in a place like Israel, which has no history of ethanol production whatsoever, you have to start somewhere,” he says. According to Gerchman, the proposals for ethanol production in Israel focus on raw materials such as pruning waste, which are available in large quantities throughout the year. However, unlike watermelons, the production of ethanol from other materials requires complex early treatment.

Although the researchers did not perform a comprehensive economic analysis to test the profitability of ethanol production from watermelons, in Gerchman’s opinion, it would still be economically viable. “In today’s ethanol industry, most of the cost lies in the raw material, which in this case is free,” he concludes.

This ZAVIT article was also published in Ynetnews on 07/25/2020.