Will Wastewater Suffice?

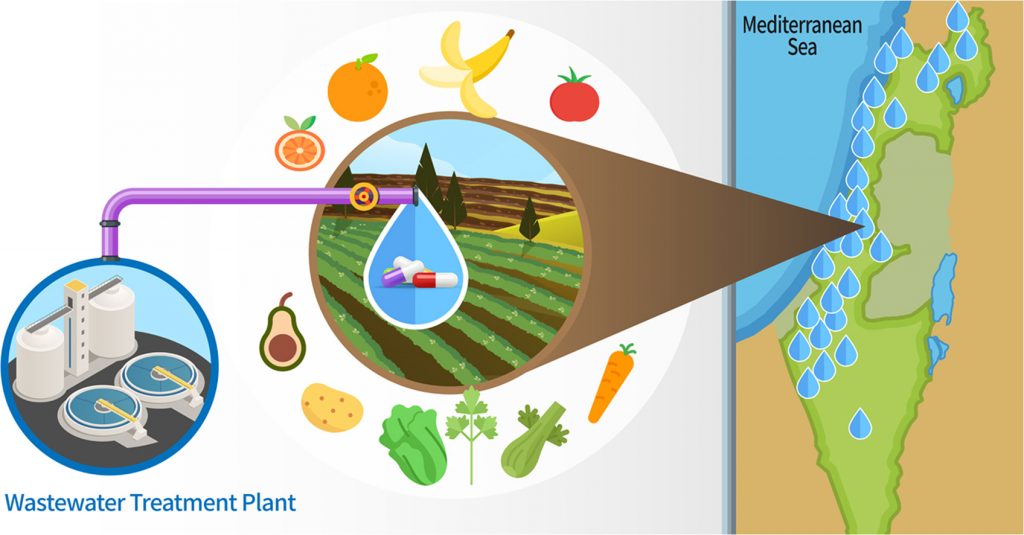

September 5, 2021To alleviate concerns over water scarcity, wastewater reclamation has emerged as a trusty solution to provide adequate water resources. But even after rounds of treatment procedures, is it safe to use? New Israeli research sheds light on the issue.

Between the hot, blistering summers, the severe lack of precipitation, and the copious amount of sunshine hours, it should come as no surprise that Israel’s climate conditions present a handful of challenges to daily life from personal errands to industrial activities. As concerns echo each year regarding whether municipal and household demand for water will be met, chronic water scarcity is still Israel’s leading climate-induced issue. With its population and standard of living rising, so does the demand for the domestic use of water. Coupled with frequent and long-lasting drought periods, Israel’s situation is far from ideal. However, its diminished supply of available water has fueled a wide variety of innovative water-saving strategies across many of its industries to compensate for its barely sufficient supply of natural water.

Israel’s most prominent workarounds are desalination and wastewater reclamation. While desalination is used to produce enough safe-to-drink water to satisfy national demand, reclaiming and recycling municipal wastewater does wonders for the agriculture sector, which in most regions of the world hogs 70% of available freshwater. Israel’s agriculture sector consumes 50% of its water by comparison––about one billion cubic meters every year. This has proven to be quite the popular method because by irrigating crops with recycled wastewater and excess stormwater, it does not deprive people of available drinking water.

By 2015, Israel had managed to treat and recycle 86% of its wastewater for agriculture, causing it to become the world’s leading nation in water reclamation. Now, Israel reuses about 90% of its wastewater effluent for its agricultural operations, and about 10% of that is divided between the country’s efforts to restore river flows and fight fires. With over $700 million dollars’ worth of investments already made in the last 20 years and the capacity to implement advanced tertiary treatment on top of primary and secondary treatment, wastewater reclamation has provided Israel an avenue for stimulating economic growth while bolstering the country’s resilience to the extreme drought conditions brought on by climate change.

But is this an airtight strategy? In May of 2021, researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem published their findings that revealed significant traces of pharmaceuticals in irrigated wastewater, soils, leafy greens, and produce from commercial fields. This gives rise to the question: how can we continue to sustainably produce agricultural products without putting the consumer’s health at risk?

Not Without Its Risks

Following primary treatment, which filters out 50%-70% suspended solids like grit, debris, and oils, the wastewater must undergo secondary treatment to break down dissolved and other suspended biosolids before being used for irrigation. However, while these treatment procedures do improve the quality of wastewater, they often do not purify the water enough to safely irrigate agricultural crops. Enough is the operative word there; it can be sufficient but there is room for error. These include people coming in contact with products contaminated by insufficiently treated wastewater, pathogens being transported via spray irrigation onto fresh edible crops, and the potential for cross contamination between the supply lines of insufficiently treated wastewater and potable water.

Tertiary treatment, however, nullifies these risks through sand or membrane filtration and additional disinfecting treatments to remove any remaining microbiological contaminants from the water. After this entire purification process, it can be distributed to the agriculture sector for vegetable crop irrigation as well as a number of other industries that need clean water such as paper and textiles manufacturing.

But for a country that reuses the vast majority of its wastewater, how can contamination risks slip through the cracks? For one, all aspects of wastewater reclamation are overseen by multiple government institutions as opposed to a single governmental body. Supervising and financing development projects, allocating treated wastewater, and creating public health guidelines are just some of the many responsibilities split up between Israel’s Water Commission and various government ministries. Although this division seems ideal, in practice, it has made the process quite problematic as Israeli law lacks clarity, which has given rise to overlapping responsibilities and thus confusion and inefficiency.

Administrative discrepancies aside, wastewater issues have been kept to a minimum, but as recent findings suggest, Israel’s edible crops might not be as contaminant-free as we expect.

Research Reveals All

According to new research from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, pharmaceutical contaminants were found in every sample of irrigated water, soil, or produce from all 445 tested commercial fields. However, it is not the first time an incident like this has cropped up.

In an earlier separate study, eight types of pesticide residues were found in cow’s and goat’s milk samples from different Israeli dairy companies where concentrations of different drug residues ranged anywhere from 0.03 (Ibuprofen) to 24 (caffeine residues) micrograms per liter. The origin of these substances was believed to have, in part, come from animal feed that was grown and irrigated with purified sewage, not uncommon for dairy production. In response, the Ministry of Agriculture handled the situation by assuring that the public health risk posed by the contents found in the milk were negligible and at such minimal levels that they did not threaten consumer health.

The researchers of this most recent study, however, focus on edible fruit and vegetable crops, including carrots, tomatoes, oranges, tangerines, bananas, potatoes, avocados, and leafy greens due to their dominance in Israel’s reclaimed wastewater-irrigated fields. Their chemical compound examination was based on the medications used in Israel, which included acetaminophen (commonly used to treat fevers), erythromycin (an antibiotic), and caffeine.

The study’s results concluded that 99% of the produce samples showed quantifiable levels of pharmaceuticals and other contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) with leafy greens containing the highest number of detectable compounds. One of the most prevalent pharmaceutical products, anticonvulsants––drugs used to prevent epileptic fits and seizures––were found in more than 90% of irrigation water and soil samples as well. Even in soil samples, the figures were staggering. There were anywhere from 1-21 contaminants in a single sample of soil and up to 46 in the irrigation water. Not one sample was free of them. The crop samples, on the other hand, had between 6 (banana) to 18 contaminants (leafy greens).

It is important to note that the prevalence of contaminants in irrigation water does not necessarily translate to prevalence in the soil; for example, stimulants such as nicotine or caffeine were detected in 96% of irrigation water samples, with only 8% of the soil samples actually containing these compounds. This is just one of the many intriguing results of this research, which continues to challenge scientists to discover how contaminants find their way from the water to the soil and ultimately into the crops we consume on a daily basis.

Consider Ourselves Lucky

In the end, the research indicates that the high-quality irrigation water used in the Negev district, which received soil-aquifer treatment, enabled produce to grow with lower concentrations of fewer pharmaceuticals and CECs. Although pharmaceuticals and CECs were detected in all water, soil, and crop samples, there are still many confounding variables and factors that influence a plant’s uptake of these compounds.

It’s unfortunate that even with all the advanced filtration systems and treatment processes we have at our disposal, we cannot completely rid recycled wastewater of all of its contaminants. And it’s not like current and soon-to-be water-deprived countries have much of a choice either way. According to UNESCO, 40% of the world’s population is projected to suffer from severe water shortages by 2050. The demand for pharmaceutical drugs is not changing anytime soon either, so we should consider ourselves lucky that the concentrations found in the food we eat are not considered harmful to us and pose no remarkable public health risk.

But this is not to say we are left without options. We can reduce human exposure to trace concentrations of pharmaceuticals and CECs by further upgrading wastewater treatment, growing crops in organic matter-rich soils, and perhaps redirecting a large share of irrigated wastewater supply to non-edible crops and “energy crops” for biofuels.

This ZAVIT Article was also published in NoCamels on 30 Aug. 2021