With jellyfish against microplastics

November 27, 2018A new Israeli venture seeks to address two major problems awaiting us at sea: jellyfish and microplastics

There nothing like a nice late summer dip along the shores of the Mediterranean sea, especially while temperatures are still high. However, very much to the dismay of many beachgoers in Israel, there is another species who thinks likewise. A scenario most swimmers are undoubtedly familiar with; as you are swimming your laps or splashing around, something is floating close to the surface of the water suddenly touches you and makes you flinch. On closer examination, you find out it is either a piece of plastic, most likely a plastic bag, or a jellyfish; an unpleasant encounter either way, although former has obviously no place in the sea and should make every bather concerned. Nevertheless, it is true that a brush with jellyfish can be a very irritating experience, and not uncommonly end with excruciating burns.

However, jellyfish might soon become our allies in the battle against a bigger threat -microplastic pollution-

Mucus filters for plastic particles

Israeli researchers are trying to use jellyfish to treat the ever-growing microplastic problem in the Mediterranean. Microplastics are microscopic plastic particles smaller than 0.5 mm in size, floating in the oceans currents, endangering marine animals of all size. The primary sources of microplastics include larger plastic debris that degrades into smaller bits and tiny pieces of plastic known as microbeads, which are added to some health and beauty products such as cleansers and toothpaste.

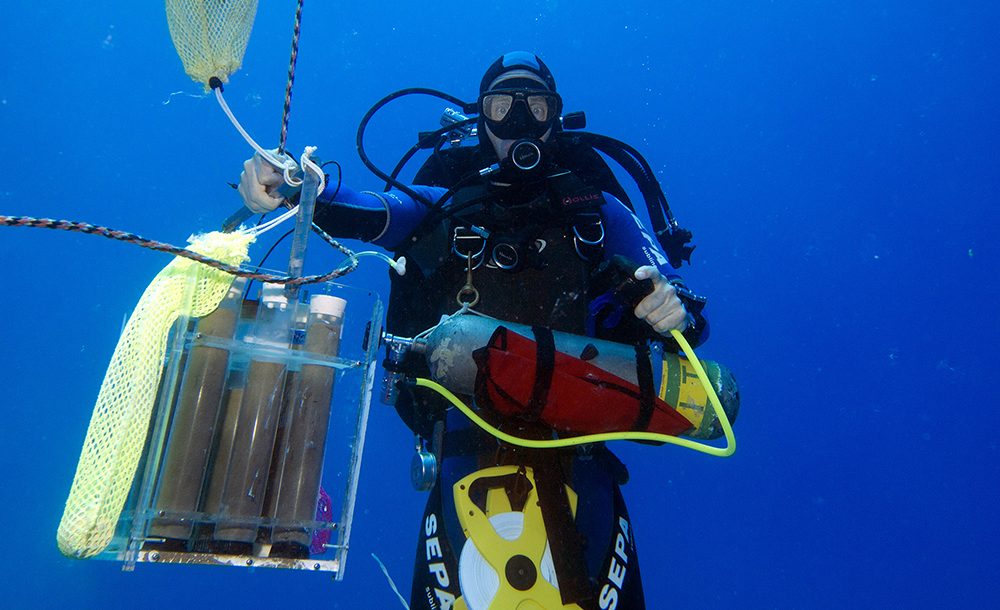

The research is part of the European project “GoJelly,” and is led by Dr. Dror Angel of the Department of Marine Civilizations at the School of Marine Sciences at the University of Haifa, in cooperation with researchers from ORT Braude College. “GoJelly deals with two important issues in the oceans today: microplastics and jellyfish,” says Angel.

The project is based on the findings of a study dating back to 2015, in which researchers were able to use mucus produced by jellyfish to isolate tiny gold particles from an aquatic solution. Angel and his team believe that jellyfish can also be used to isolate microplastic particles from the water, thus turning the tide in our favor. To this end, the researchers extract mucus from the jellyfish and apply it to experimental setups in the laboratory, trying to see if the mucus can cause the microplastic particles to stick and thus removing them from the water. In the future, Angel and his team hope to be able to apply those filters in wastewater treatment plants, which might be a primary source of ocean microplastic pollution or at least one that can be tracked down.

Photo by Willian-Justen on Unsplash

Photo by Willian-Justen on Unsplash

”There is a lot of microplastic waste that goes into the urban sewage system and from there into wastewater treatment plants,” says Angel.” “In many countries treated water goes directly into rivers and ultimately into the sea, which makes those plants a potential source of microplastics and a rather tangible opportunity to trap the particles before going into the sea, Angel continues.”

The water that is being treated in these facilities undergoes a process designed to clean it of contaminants, but tiny plastic particles are often not removed during the process due to insufficient filter systems (even though the facilities use the best available technology). In most wastewater treatment plants in the world, the water is discharged into the sea after the treatment. “That’s how we constantly add more microplastic particles to the oceans, along with the treated water,” says Angel.

While Angel and his team are in charge of the jellyfish research, another group consisting of civil engineers from ORT Braude College are taking a closer look at the treatment plants. Their goal is to determine what types of microplastics are present in the plants and in which stage of the treatment process it would be most suitable to implement the futuristic jellyfish-filters.

According to Angle, part of what makes the project so challenging is that even the collection of the microplastics from the plants for testing is not a trivial matter and requires the development of technology specifically for that purpose. “Everything is new in a way, especially since we are also interested in the very smallest microplastic particles that come out of the treatment plants, for which we need an even more futuristic approach because there is no really good technology at the moment to quantify this material.

Plastic particles may reach the food web

In Israel, however, the treated wastewater is not flowing into the sea, but it is used for agricultural purposes, which adds another element to the problem. As one of the leading countries in the reuse of water, Israel recycles almost 90 percent of its wastewater, most of which is used for irrigation. “If water containing microplastics is used to irrigate crops, the particles may enter the root and reach the plant tissue, in which case they would be present in the food we consume,” says Angel.

So far, little is known about the human health effects upon ingesting microplastics. Nevertheless, marine animals are known to frequently ingest microplastic particles because they appear similar to their natural foods. In a report released last year, Israeli researchers found significant amounts of microplastics in the digestive tracts of 81 out of 88 tested rabbitfish, which is one of the most common herbivorous fish along Israel’s Mediterranean coast. Additionally, plastic particles may reach the food web through many other animals that feed on directly exposed animals. Occasionally, persistent organic pollutants, which do not dissolve in water and potentially harm animals, adhere to microplastics. Other materials found in plastics and known for their adverse health effects are Bisphenol Aand phthalates. These substances accumulate in the body of the animal over an extended period and thus may impair hormonal processes and even reduce the survival rate of the species.

Photo by Willian-Justen on Unsplash

Photo by Willian-Justen on Unsplash

”We actively helped the jellyfish to thrive”

As if Angel’s teams were not struggling with enough challenges, this year, the researchers were facing the rare problem of not finding enough jellyfish for their tests. “One of the hardships we are experiencing this year is that we expected a jellyfish bloom in July, which we could harvest mucus from to test the idea. However, the jellyfish never really bloomed, which set us back a bit. Something funny is going on because now they came back in September, but in smaller numbers and even smaller size, which is anomalous, so we are clearly limited in our possibilities,” Angel says.

At the moment it is not clear why the jellyfish exhibit such unusual behavior, but the fact that large outbreaks typically recur around the same time in Israel, makes it all the more puzzling.

For three decades, Israel has been struggling with large jellyfish summer blooms, and the constant outbreaks have become an ever-growing problem, primarily due to species that do not even belong in the Mediterranean.

The most common jellyfish on the coast of Israel is the nomad jellyfish (Rhopilema nomadica), an invasive species, and a descendent from the Indian Ocean. Subsequently to the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, connecting the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea, the nomad jellyfish arrived from the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean several decades ago, similar to many other migratory species. Normally jellyfish appear in Israel during the summer months between May and August, although this year, jellyfish have been observed in the hot days of April. In recent years, swarms of jellyfish came to the beaches even during the winter.

In the last three decades, Mediterranean Sea temperatures have risen by three degrees, which has allowed jellyfish to thrive. Jellyfish that have invaded local Israeli waters from the Indian Ocean, where sea surface temperatures are naturally higher, might feel very comfortable when waters get warmer. Angel stresses that even beyond the effects of climate change, human actions are a significant factor in the increase in the quantities of jellyfish. He says that men broke the balance of the sea. “We did things that stimulated the proliferation of jellyfish, like overfishing those fish that compete with them for food. We actively helped the jellyfish to thrive,” he says.

At the moment, the research of Angel and his team is still in its early stages. The scientists are now focusing on the best production method of the jellyfish mucus, and an in-depth examination of the particles present in the water at each stage of the wastewater treatment procedure. Until the study progresses into more practical steps, the jellyfish will wait for us out at sea. Regarding microplastics, however, everyone can contribute their share and reduce the number of plastic products we consume, and avoid dumping waste in the coastal and marine environment.