Out of sight, out of mind

June 13, 2018For the first time, scientists set out to study the abundance of microplastic particles in Israel’s Mediterranean coastal waters. New "plastic bag law" shows promising results

By now, most of us know that there is an alarming amount of plastic floating around in our oceans in many shapes and forms. Word is that by 2050 there will be more plastic in the oceans than fish if waste disposal issues are not adequately addressed.

Thanks to countless studies in recent years, we are now drawing ever closer to having an approximate idea of the actual extent of marine plastic pollution. From the North Atlantic to the South Pacific, from the Bay of Bengal to the South China Sea, studies have found massive amounts of marine plastic debris, lots of it concentrated within the five subtropical ocean currents.

It is estimated that a third of all the discarded plastic winds up somewhere it does not belong – above all, in the oceans. The magnitude of the pollution may not be easy to fathom, but considering that in 2015, global plastic production exceeded 300 million tons, one might be able to get a vague idea.

We have all seen images of entangled seals and turtles. Almost everyone has heard horror stories of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an enormous accumulation zone of marine debris in the North Pacific Ocean, spanning approximately 0.7 million square kilometers. The unpopular truth of plastic is blatantly flaunting its ugly face on the news and the internet every day. Sadly, these are images we all have gotten used to already. However, we also know that there is a second layer of the problem, which lies beyond what we perceive.

Invisible to the eye, microplastics are rife in the world’s oceans and could potentially have more far-reaching impacts than regular-sized pieces of marine litter. Some 92% of the ocean’s plastic is smaller than 5mm in size and therefore classified as microplastics, with nanoplastics being even smaller.

These tiny particles, which are often ingested by small aquatic organisms, might travel up the food chain all the way to the big game fish, and yes, onto our plates. Although the long-term effects on humans are yet unknown and consequences remain speculation, scientists believe the particles may adsorb and concentrate toxic substances before getting ingested by the marine animals.

Trash eventually breaks down into microplastics

Numerous studies have demonstrated a high abundance of plastic debris in the Mediterranean Sea. Several computer models predicted it to be more impacted by floating plastic than any other large body of water. This pollution is attributed mainly to human activities, such as tourism, shipping and rapid development along coastlines, paired with a scant outflow of surface water into the Atlantic Ocean.

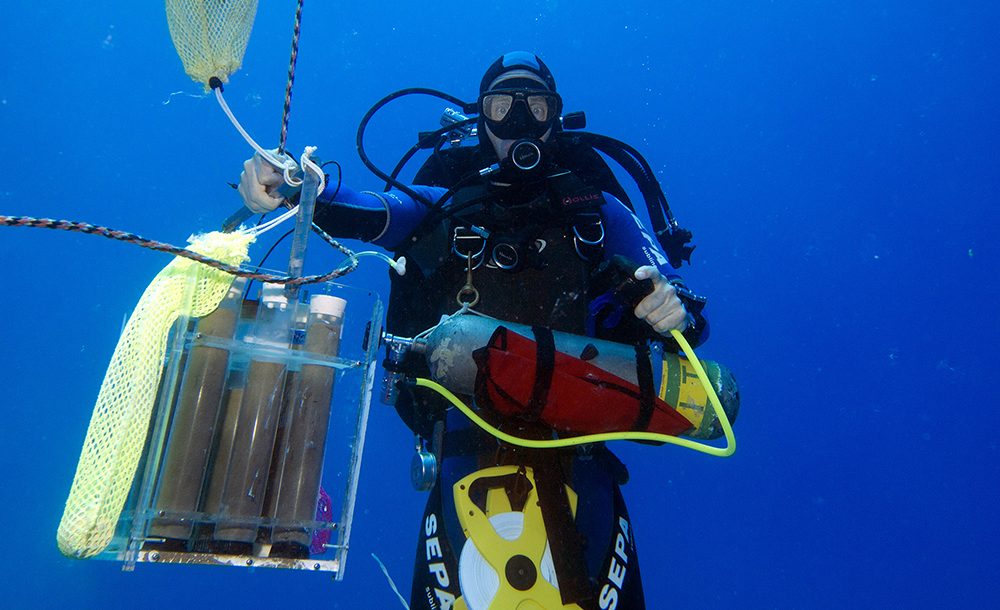

However, until recently, most of the data on synthetic polymers including microplastics in the Mediterranean came from the Western Basin, while the eastern side had gone virtually unstudied. Now, for the first time, the abundance of microplastics along the Israeli coast has been sampled and quantified. As expected, the results are everything but encouraging.

The overall message of the study is clear. “Microplastic debris is highly abundant in Israeli coastal waters. According to the study, conducted by Noam Van Der Hal, a Ph.D. student at the Department of Maritime Civilizations, University of Haifa, under the supervision of Dr. Dror Angel, the mean abundance of microplastics found along the Israeli coastline is not only high compared to other parts of the world but is edging out the rest of the Mediterranean Sea. 94,417 particles ranging between 0.3-5 mm were found in a total of 108 samples.

In an interview, Van Der Hal states that “a large volume of the plastic debris enters the sea through rivers and municipal pipelines. Surface runoff picks up everything that is light enough to float, including plastic wrappers, packaging, bottles, and caps.”

Much of the plastic loses its flexibility by the time it enters the water and can crack easily. Subject to sunlight and continuous wave action, a great deal of that trash eventually breaks down into microplastic particles. Currents play a decisive role in the distribution of the fragments, and marine debris may come from other areas.

“Since this is the first time we conducted a study on microplastics in this area, a lot remains unclear, and further research is required,” says Van Der Hal. “Although we believe that most of the microplastics along the Israeli coast is homemade, some of it may arrive here by northward currents from the Nile Delta or through Western Winds blowing from the open sea. Some of it might even find its way here from rivers that originate in the Taurus mountains up north.”

In a recent study, Van Der Hal and colleagues sampled and analyzed the number of microplastic particles in the digestive system of the rabbitfish (Siganus spp.), the most abundant herbivorous fish along the Israeli Mediterranean coast. 81 of 88 fish examined in the study contained significant amounts of microplastic particles, mainly in the form of fibers, fragments, and films. Despite the fact that the level of toxicity of microplastics can vary and in this case was not yet scientifically assessed, the debate over its deleterious effects is getting louder.

“A big step forward”

While Van Der Hal warns against the long-term consequences of the country’s excessive use of disposable plastic, he also points at the break in the clouds. According to Israel’s Ministry of Environment, the ban on free plastic bags in Israel’s supermarkets has already paid dividends.

“Due to fewer plastic bags sold, the amount of garbage on the beaches and in the coastal waters has supposedly already declined. If regulations on single-use articles were expanded, the volume of microplastics would consequently decline”, says Van Der Hal.

This view is shared by Galia Pasternak, a fellow Ph.D. student at the University of Haifa. Pasternak is one of the people responsible for the first beach-waste survey on Israel’s Mediterranean coast. A whopping total of 69,122 pieces of trash were recorded on eight separate beaches between 2012 and 2015.

Whereas the density of general refuse on Israeli beaches is relatively low, the volume of plastic waste is high. According to the study, 32% of all the debris is made up of food wrappers and disposables, followed by plastic bags (23%) and cigarette butts (16%).

Pasternak says beach litter in the form of food wrappers and disposables remains the greatest problems for Israel and the Mediterranean, exceeding the global average two-fold. “However, the number of plastic bags we observed in summer 2017 was only half of what we found in 2016,” says Pasternak.

That is particularly important because at the time the 2016 survey was carried out, synthetic bags were not yet subject to regulation and therefore critically affected the study’s results. Furthermore, Pasternak suggests a ban on plastic straws in cafes and stands along the beaches. “Every coffee shop and kiosk has a contract with the municipality. If they implemented an article that prohibits or at least limits the sale of plastic straws, we would make another big step forward,” she adds.

The government-funded “Clean Coast Program” has already been making a change through a combination of frequent beach clean-ups, educational activities and improved enforcement against littering. Nonetheless, according to Pasternak as well as Van Der Hal, more has to be done in the form of regulations if we really want to see a lasting shift toward plastic-free oceans.